By Ines Kagubare

In recent years, several young men and women from western countries such as the U.K. and the U.S. have traveled to Syria and Iraq to join the terrorist group known as ISIS. According to the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, there are currently more than 20,000 foreign fighters who have joined ISIS in the past year. About 150 foreign fighters are American citizens while another 4000 are from Western Europe. Most of these fighters are in their late teens and early 20’s. Most of these foreign fighters are crossing the Turkish border in order to join ISIS camps in Syria and Iraq. ISIS leaders have promised these young fighters that they will be treated well once they arrive there and that their lives will be much better than where they are coming from. They also remind them that they are fighting for a just cause and that they should be willing to do anything, even if it’s geared towards violence, to protect the religion of Islam.

The question still remains, why do all these young fighters, especially women, want to leave their somewhat comfortable lives to join ISIS. I use the word “somewhat” because some of these young fighters who are leaving countries such as the U.K. and the U.S. might not necessarily live comfortable lives. Most of them live in poor neighborhoods that are racially and ethnically segregated. Some of them drop out of school and are unemployed. They have limited opportunities to succeed in life, which leads them to have no hope, no ambitions or goals for their future. There are some exceptions of those who are successful and have a bright future ahead of them but still choose to join terrorists groups such as ISIS. Those who are impoverished don’t feel appreciated and are sometimes discriminated against by the country they call home, which leads them to despair and that’s why these young fighters think they will find comfort from their struggles when they join ISIS. They believe that ISIS will provide them with opportunities they lacked back in their home country.

For them, ISIS is an exciting, adventurous group that has a mission and a purpose that they previously did not have. ISIS “preys on a recruit’s sense of identity,” said CNN writer Holly Yan. They feel that they finally belong in a community that appreciates them compared to the western society where they felt isolated and treated as outsiders in their own country no matter what how hard they tried to assimilate. One can also argue that they feel a sense of patriotism and pride of their Muslim heritage that they cannot fully express living in western countries since they are a minority compared to the majority who are Christians.

One aspect of this issue that has been raised is the role of women in ISIS. There has been an increasingly number of young girls in their late teens traveling to Syria and Iraq to join ISIS. Why do they willingly decide to join this terrorist group and what purpose do they serve is still unclear at this time. Many of these young girls are still in school and they have never been in trouble with the law. Their families are as shocked as law enforcement about their daughters’ decision to join a terrorist group such as ISIS. The parents were unaware of their daughters’ plans and did not notice any red flags that could have indicated that they had become radicalized. They may or may not know that their freedom will be restricted and that they will have to submit to men. Most of these Muslim nations, especially Saudi Arabia, treat women as second-class citizens and not as equals. It’s difficult to determine if these young girls are simply naïve or if they know exactly what situation they’re getting themselves into and that they are ready to face the consequences once they join ISIS.

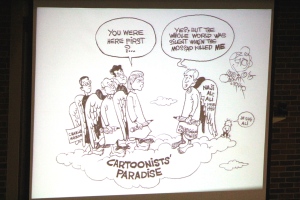

The first step in resolving any problem is to understand the roots of its cause. Once we have a solid understanding of the issue (although it’s not always simple) we can determine the various steps we can take to find effective solutions that will work in the long run. It’s not by using drones to kill ISIS leaders that we are going to stabilize the region and reduce the threat of terrorism overnight. On the contrary, the more we engage with them using drone strikes the more radicalized extremists want to join terrorist groups such as ISIS. Killing one leader will only generate more hatred and bring about more leaders and fighters. It becomes a vicious cycle that everyone is trapped under because we are only focusing on short-term solutions that benefit us in the present and not really looking for long-term solutions that will benefit future generations.