By Lily Cusack

Beirut Bombings

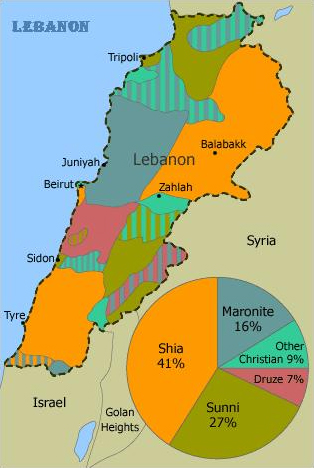

On Thursday, two suicide bombings took place in Beirut, Lebanon. According to CNN, the bombs killed at least 43 people and injured another 239. The explosions took place within 490 feet of each other, and they each happened within five minutes. They damaged at least four buildings near the explosions. There were three attackers, but two of them died during the bombings. The third bomber told authorities they were ISIS recruits that had arrived from Syria two days prior to the incident. Authorities say the militants could be part of a cell that ISIS dispatched to Beirut. The explosions went off in an area where the Shiite militia has a solid presence. One of the attackers tried to enter a Shiite mosque, but was prevented by security. Friday was declared a day of mourning for Lebanon.

Thursday’s bombing attack took place in Beirut, Lebanon. Courtesy of Wikipedia.com.

Jihadi John

The Pentagon said on Thursday that they are “reasonably certain” that ISIS militant “Jihadi John” was killed during a drone strike in Syria, according to BBC News. Kuwaiti native and British militant Mohammed Emwazi, also known as “Jihadi John,” was seen in many videos of the massacres of ISIS hostages. The first video he appeared was of the murder of US journalist James Foley last August. He has also been a part of the videos showing the killings of U.S. journalist Steven Sotloff, British aid worker David Haines, British taxi driver Alan Henning, American aid worker Abdul-Rahman Kassig, and Japanese journalist Kenji Goto. He was also seen during the mass beheading of Syrian troops. Three drones, one British and two American, carried out the attack during routine attacks that have been performed against ISIS leaders since May.

Paris Terror Attacks

A series of terrorist attacks took place Friday night in Paris. According to The Telegraph, the seven coordinated attacks occurred in the center of the capital, killing at least 132 and injuring another 352. Seven militants, all wearing suicide vests, have been linked to the attacks. The first two explosions were located at the Stade de France during the first half of the France-Germany soccer match.

The explosions went off between 9:20 and 9:30 p.m., minutes apart from each other. The explosions killed one person along with the two militants that detonated their suicide vests. French President François Hollande was in the crowd watching the match, and he was promptly escorted out of the stadium. At 9:25 p.m., gunmen opened fire on Petit Cambodge Cambodian restaurant and Le Carillon bar on Rue Bichet, about four miles from the stadium. Fifteen people died in the attack. The same gunman then drove to Rue de la Fontaine au Roi where they killed at least five at Casa Nostra pizzeria. The fifth attack happened on Rue de Charonne at La Belle Equipe bar at 9:40 p.m. where at least 19 people died. The militant detonated his suicide vest around the corner from the bar on Boulevard Voltaire. At around 9:50 p.m., three militants entered the Bataclan concert venue on Boulevard Voltaire, about a mile away from the restaurant shootings, where the U.S. rock group Eagles of Death Metal was performing to a full house of 1,500 people. The gunmen were brandishing AK-47 rifles and suicide vests.

The siege lasted two hours and 40 minutes as they held the venue hostage. Anti-terror police ended the hostage crisis at around 12:30 a.m. Two of the militants detonated their vests, and the police shot one. The death toll rose to 89. The last attack took place at around 10 p.m. where a militant detonated his vest near the Stade de France outside of a McDonald’s restaurant. One person was seriously injured.

Myanmar General Election

Aung San Suu Kyi and her party, the National League for Democracy (NLD), were declared victorious on Friday after the votes were tallied for the Myanmar general election. The party won a majority of seats in parliament, with 348 seats across the lower and upper houses, according to The Guardian. This is 19 more seats required for an absolute majority. The victory for Suu Kyi marked the end of a half a century of military dominance in the country. Although Suu Kyi is banned from presidency due to the country’s constitution, the NLD will be able to push their own legislation, form a government and pick a president of their choosing. This administration will be the first government since 1960 not picked by the military and their political allies. The current government officials have accepted their defeat, and say they are willing to work on handing their power over peacefully. Army generals still control the most powerful aspects of government: interior, defense and border undertakings.

Aung San Suu Kyi, National League for Democracy part leader. Courtesy of Wikipedia.com.

Japanese Earthquake and Tsunami

An earthquake and a tsunami occurred off the coast of Japan early Saturday morning. According to IB Times, the earthquake was a 7.0 magnitude, and its epicenter was just under 100 miles southwest of the town of Makurazaki, occurring at a depth of about 6 miles. A one-foot tsunami hit the Japanese island of Nakanoshima as a result of the earthquake. However, there were no reports of damages or injuries. The Japanese Met Agency announced a tsunami advisory, but it was canceled after an hour and a half.

Just a few days later, on Nov. 9, 1989, the demonstrators would be rewarded. Mounting pressure to deal with an increasing number of refugees, combined with a breakdown in communication between party officials, led East Germans to begin gathering at checkpoints along the wall. They believed that a new policy had been announced, allowing them to cross over into West Berlin. Overwhelmed by the crowds, and without orders from their superiors on how to deal with them, border security allowed them to pass through.

Just a few days later, on Nov. 9, 1989, the demonstrators would be rewarded. Mounting pressure to deal with an increasing number of refugees, combined with a breakdown in communication between party officials, led East Germans to begin gathering at checkpoints along the wall. They believed that a new policy had been announced, allowing them to cross over into West Berlin. Overwhelmed by the crowds, and without orders from their superiors on how to deal with them, border security allowed them to pass through.