By Ines Kagubare

It’s been more than five years since the Civil War in Syria began during the Arab Spring uprisings. Unlike other countries such as Tunisia, Egypt and Libya who successfully overthrew their dictators, Syria has been unable to depose its current leader, Bashar al-Assad. Instead the revolt has led to a refugee crisis that’s now spreading throughout the region and across Europe.

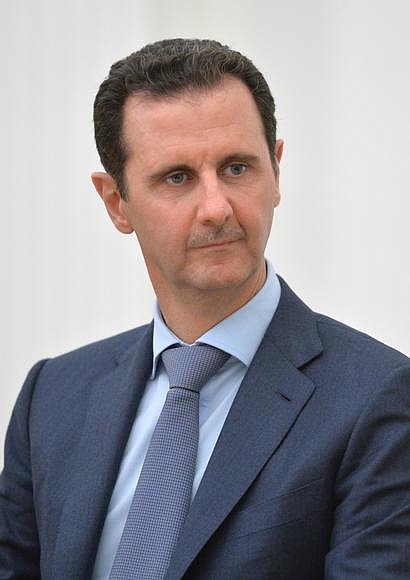

Syrian president Bashar al-Assad. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

More than 1,000,000 refugees and migrants are currently seeking asylum in the European Union. Before I go on, let’s make a distinction between refugees and migrants. Refugees are fleeing their country of origin usually because of war or a natural disaster whereas migrants are choosing to settle in another country for economic opportunities.

Syrians make up one of the largest populations of refugees seeking asylum. Most of them are fleeing their country to escape the Assad regime and the ongoing violence caused by Muslim extremist groups like ISIS. According to Eurostat, “Syrians accounted for almost a third [of refugees] with 362,775 people seeking shelter in Europe, followed by Afghans and Iraqis.” According to the IOM, roughly 1,011,700 migrants arrived by sea while 34,900 arrived by land in 2015. Those arriving by sea usually cross the Mediterranean from Africa to Italy or Greece. While those arriving by land usually pass through Turkey from the Middle East to Europe. More than 3,770 migrants died trying to cross the Mediterranean Sea in 2015, according to IOM.

Syrian refugees strike in front of Budapest Keleti railway station. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

The European Union has tried to implement refugee-friendly policies that would make it easier for refugees to receive asylums. According to the BBC and Eurostat data, “Germany received the highest amount of new asylum applications (higher than any other EU nation) in 2015, with more than 476,000”. They were closely followed by Hungary and Sweden in numbers.

Although it seems that the EU is taking a step in the right direction in terms of helping refugees find new homes, they haven’t taken as many migrants as countries such as Italy, Greece, and Hungary. Since these are the first nations where migrants arrive by sea and land, they have incurred more people hoping to find refuge than other countries. The EU is planning to relocate 160,000 migrants to some of its nations that have fewer refugees in order to lessen the burden of countries that have an abundance of them.

The new EU refugee policy hasn’t come without controversy or backlash from far-right groups across Europe such as Pegida, Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamization of the West, who portray refugees and migrants as “invaders.” They believe that refugees settling in Germany will take over and destroy their culture. They have been very critical of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision of granting asylum to more than 100,000 refugees.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

As of 2015, the EU has granted 292,540 asylums to refugees mostly coming from Syria, Eritrea, Iraq and Afghanistan.

Just a few days later, on Nov. 9, 1989, the demonstrators would be rewarded. Mounting pressure to deal with an increasing number of refugees, combined with a breakdown in communication between party officials, led East Germans to begin gathering at checkpoints along the wall. They believed that a new policy had been announced, allowing them to cross over into West Berlin. Overwhelmed by the crowds, and without orders from their superiors on how to deal with them, border security allowed them to pass through.

Just a few days later, on Nov. 9, 1989, the demonstrators would be rewarded. Mounting pressure to deal with an increasing number of refugees, combined with a breakdown in communication between party officials, led East Germans to begin gathering at checkpoints along the wall. They believed that a new policy had been announced, allowing them to cross over into West Berlin. Overwhelmed by the crowds, and without orders from their superiors on how to deal with them, border security allowed them to pass through.